|

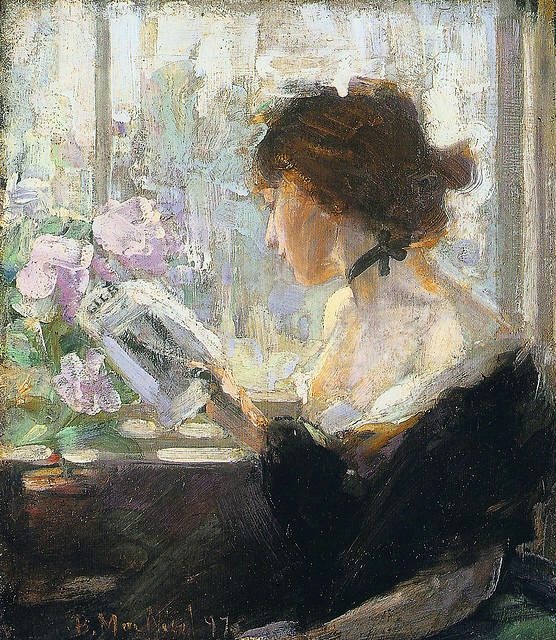

| Autumn, by Bessie MacNicol, c. 1898. (image via). |

When I visited Scotland a few years ago I was unprepared for how much I'd like Glasgow; it's the kind of unassuming city that truly cool people call their hometown. So when I read about the Glasgow School of Arts and its community that flourished around 1880-1920 I'm honestly kind of jealous. Frances Henry "Fra" Newbery was an influential teacher who was by all accounts very fun, who encouraged male and female students and teachers alike. Students were often seen stitching feminist banners between classes; this is primarily because the needlepoint teacher was an active member of the militant wing of the Women's Suffrage movement who did several stints in prison, though no one knew exactly what for (she'd used an assumed name). They held historic costume pageants and wore each other's art nouveau designs. Students formed lasting friendships. Everyone who attended seemed to open studios on the same streets and holiday in the same artist colony in Kirkcudbright.

The School was so productive that it helped Glasgow gain an international visibility in the art world. Previously Scotland's reputation orbited Edinburgh and its schools' more conservative Romantic art. Then there were three waves of Glasgow artists, plus a design movement, that put Glasgow on the map.

The first wave were inspired by the Barbizon school in France, where artists painted en plein aire (i.e. outside) from nature and left paint surfaces slightly sketchy or patchy rather than thin and carefully blended. The Glasgow artists valued "realism," which in this case means portraying the world around them (farmers, landscapes and real people doing everyday things in the painters' own era). This summarizes both the critics' take on the movement and the manifestos of painters themselves, but I have to admit I have a hard time wrapping my mind around it. To me the paintings do look idealized: quaint bucolic tableaux, attractive peasants, vaguely fairy-tale versions of Scotland's yesteryear. And all that warm glowing sunshine! Having been to Glasgow, I can tell you that is not realistic. However, compared to the contemporaneous Parisian Academic style (scenes from Classical Greece, religious allegory and idealized nudes in fantasy situations) the Glasgow painters were realistic. They shone a spotlight, however soft-focus, on Scotland's own landscape and people.

|

| A Galloway Landscape, by Bessie MacNicol, 1889. (image via) This landscape shows the influence of the first Glasgow wave on MacNicol. The piece isn't Impressionist but it is made of shimmering patches of color and the colors, while not brilliant, are rich. It shows real people in a real place. The trees on the left have a bit of a storybook quality to them. |

The second wave, around the 1890s-1900s, built on the previous wave's goals but with the added influences of the Impressionists and Glasgow's own craft and design movement. Margaret and Charles Mackintosh's famous take on Art Nouveau incorporated ancient Celtic motifs and made everything it touched into art, from writing desks to winter coats. Likewise fine art began to incorporate these Art Nouveau decorative arts. Second wave paintings, while still showcasing Scottish landscapes and people, often resembled story book illustrations, sometimes with gold leaf, outlines or or stylized figures and foliage. They professed to be inspired by Whistler.

|

| Two Sisters, by Bessie MacNicol, 1899. (image via). This shows the influence of the second wave, of which MacNicol was a part. They'd obviously absorbed the techniques and colors of Impressionism. The stylization also alluded to the crafts movement; here the figures look like they could be from a carved woodblock print, while the foliage and patches of color are reminiscent of embroidery. The emotion of the piece comes primarily from its beautiful surface and gives the subjects a deeper, more timeless symbolic meaning. |

Beginning around World War I a third wave of artists planted their modernist flag on the tradition, incorporating Fauvist and Art Deco design. This wave of art didn't even hit till after Bessie MacNicol died, I only mention it because it's super cool and you should check it out.

These three waves were collectively known as "The Glasgow Boys." However many female artists were involved, so to prevent them from being erased a group of 1960s historians coined the term "The Glasgow Girls." This refers to artists from all three waves as well as decorative designers and craftswomen. The effort turned out to be quite effective actually; scores of Scottish bloggers and historians seem genuinely excited to celebrate these "wummin." I still think it's silly to separate them here, since in real life they were all up in each other's business, so I'll just call them the Glasgow School.

When I look at the Glasgow School, here's what I see: the legacy of Symbolism and all its spin-off aesthetic movements. If you've ever taken an art history course you know about the shockingly modern Impressionists, with their audacious photography- and Japanese-inspired compositions, their frank everyday subject-matter, their innovations in form and color. And you know about the aftermath, the post-impressionists (like Cezanne) and the Fauvists (like Matisse) and Cubists (like Picasso) who eventually led to Abstract Expressionism (Rothko, Pollock). You know how all of this bucked the bourgeois tradition of Academic Painting.

While all of this was going on, another movement broke the rules of Academic Painting by looking instead to the past. Beginning with the Symbolists, these painters valued aesthetics above all else, and it shows: their paintings are dreamy. Instead of Classical Greece, these painters looked to Northern Europe's past for inspiration, such as Arthurian tales and scenes from Shakespeare. They sometimes incorporated dreams, magic, the occult and explicit sexuality, and their art usually bled into concurrent design and craft movements. I think their closest comparison today might be the pop culture witchcraft revival. Spin-off groups included, among others, the Pre-Raphaelites in England, the Nabis in France, the Arts and Crafts movement (such as William Morris) and Art Nouveau movement, and The Decadents. Of course the division between the proto-Modernist Impressionists and neo-traditionalist Symbolists wasn't really so clear-cut-- there were in-betweenies like Gauguin and Mondrian, and each movement influenced the other and overlapped in philosophies. Impressionists borrowed Japonisme and unabashed, sensuous sexuality; Symbolists borrowed Impressionist and Fauvist techniques. Maurice Denis of The Nabis wrote, "The profoundness of our emotions comes from the sufficiency of these lines and these colors to explain themselves...everything is contained in the beauty of the work."

It was into this world that Elisabeth "Bessie" MacNicol was born. Though many of her siblings died very young, including her twin, her household was stabil. Her dad was a school principal and she and her sister played music together. She adored the outdoors. When she grew up she attended the Glasgow School of Arts and thrived. It was then that she was encouraged to study in Paris to develop her outstanding talents.

Studying academically in Paris was another exciting opportunity in an novel era, because it was only a few years prior that Académie Colarossi had opened its curriculum to women. They could study anatomy from nude models right alongside men (in some accounts they used segregated studios), a crucial part of serious art education which had never before been allowed to women in Europe. The many women who had, had done so quietly and illicitly through family connections or indulgent mentors. International female students flooded in for the coveted opportunity, including a notable contingency from Scotland, among them in 1893 was MacNicol.

She hated it. She got nothing from the instruction. Compared to Fra Newbery's Glasgow School she found the instruction "restrained and repressive." She felt the teachers were trying to reduce her to the style they wanted, not to encourage her (as you may remember from my post for Inktober Day 3, this is the same school attended by Cecilia Beaux around the same time period, and the two women's accounts couldn't be more different). But MacNicol didn't waste her time in Paris. She cut quite a few classes and instead soaked up the contemporary art in the city's galleries. She was deeply influenced by the Barbizon plein aire painters, the Impressionists, and James Abbott McNeill Whistler's aesthetic realism; judging by her work probably the Nabis and Paris's Art Nouveau designers as well.

|

| French Girl, by Bessie MacNicol, 1895. (image via). You can see the influence of Impressionist painters such as Berthe Morisot and of stylish Parisiennes in the Art Nouveau era. |

When MacNicol returned to Glasgow she embraced the community of the Glasgow School of painters and their decorative pastoral realism. She acquired a studio on St. Vincent Street, where fellow "Glasgow Girls" Helen Paxton Brown and Jessie M. King shared a studio, among others. From this time forward the influence in her work of other Glasgow artists such as Edward Atkinson Hornel, a fellow second wave painter who was a bit older and more established than MacNicol.

|

| Edward Atkinson Hornel, by Bessie MacNicol, 1896. (image via Pinterest; another version here). MacNicol was especially influenced by Hornel's decorative realism. He used used his palette knife to scrape and spread his paint into heavily textured surfaces that he sometimes decorated with gold leaf and polychrome or other old techniques, but by the time MacNicol met him he's moved on to more naturalistic work with atmospheric colors and lush poetic themes. The time Hornel had spent living in Japan showed in his innovative compositions and his subjectmatter usually included myth and lore, such as his Druids Bringing In The Misteltoe. MacNicol sought him out at his studio when she spent the year at a seaside artist's colony called Kirkcudbright just outside Glasgow (where The Wicker Man was shot in 1973). Hornel commissioned this portrait from MacNicol. You can see the surface is especially scritchy-scratchy, a reference to his signature textured techniques. |

A lifelong lover of the outdoors, MacNicol soon distinguished herself as a painter of radiant lighting effects such as dappled sunlight through leaves. Alternately she'd illuminate her indoor subjects with dim moody casts. She was clearly influenced by plein aire techniques, but I don't know if she practiced it, or incorporated a mix of outdoor studies and indoor studio work as many artists did. Oil paints and watercolors were her strong preference.

|

| Under the Apple Tree, by Bessie MacNicol, 1899. (image via). This is one of MacNicol's most famous pieces, exemplifying the dappled lighting and outdoor portrait setting she was known for. |

|

| Elizabeth Reading, by Bessie MacNicol, 1897. (image via). |

|

| Lamplight, by Bessie MacNicol, c. 1900. (image via). |

|

| Lady with a Lace Collar, by Bessie MacNicol. (image via). |

MacNicol married a physician and fellow artist named Andrew Frew in 1899 and moved to the Hillhead neighborhood, Glasgow, where she set up a home studio. Her success continued and she was very well-known in her lifetime, considered "the most important female artist in Glasgow." Her work was widely exhibited in her lifetime in Glasgow and London, and in some European and American cities.

|

| In The Greenwood, attributed to Bessie MacNicol. (image via). |

|

| The Visit, by Bessie MacNicol. (image via) |

|

| Portrait of a Lady, by Bessie MacNicol. (image via). |

Tragedy hit the couple in 1903 when MacNicol's parents died. The following year MacNicol died in childbirth or the late stages of pregnancy. She was just 34.

Her

husband was devastated. He remarried four years later in 1908 but killed himself shortly

afterward. His grieving widow was then left with MacNicol's art and estate, so she did what anyone would do and sold it all off as fast as possible, within the year. Unfortunately that means the whearabouts of many pieces is unknown and or scattered across private collections (instead of displayed in museums and easily available online; many pieces of her art exist online only as obscure remnants of past auctions).

Some of it has even turned up in Vienna and St. Louis. But she does have pieces available to see in person at the Kelvingrove in Glasgow. We have almost no personal ephemera from her life, like photos and letters.

|

| Portrait of Peggie, by Bessie MacNicol, 1899. (image via) |

|

| Lady with a Fur Collar, by Bessie MacNicol, 1904. (image via) |

|

| The Fur Coat, by Bessie MacNicol. (image via). This is a fun one; it looks like a magazine advertisement featuring a "Gibson Girl" or "Brinkley Girl." I love the way the snow is painted and the rich black form against it. |

|

| Vanity, by Bessie MacNicol, 1899. (image via). This is an unusual piece because women didn't often paint nudes at this time. Paintings of nude pretty women tend to be very decorative and sensual, but interestingly this is the least decorative of her work that I've seen. Instead its mood is more studious and its draftsmanship more ambitious; it reminds me of some late pieces by Degas that MacNicol could reasonably have seen in Paris. |

Here's my own drawing of Bessie MacNicol. I could find only one photo of her, likely because MacNicol's husband's new wife sold off her estate. I think it's from one of the Glasgow School's historic pageants, and it's kind of weird and unflattering. Luckily one of her self portraits remains, a dimly lit view of her face and neck against a black background. I wanted to replicate some of her famous lighting effects, so I used the self portrait as a basic reference, tweaked the shading a bit to appear outdoors, and then filled in details like her hair and shoulders that weren't visible the dark self portrait. I used a few of her portraits of women under trees as references to create the dappled lighting, background, headband with flowers, and clothes. I took the cue for the hair and decorative headband from the Pre-Raphaelites and other decorative Symbolist painters of MacNicols's era.

No comments:

Post a Comment